I’ve been staring at A Few Small Nips again and again, unable to look away, circling back each time to the woman’s nipples out of longing. As if I could possess such nice things on my chest. As if the most valuable thing I could offer a man was a pair of beautiful breasts, sweet and symmetrical, with faint brown and almost pink areolas. But that’s never the truth of what women give. A woman’s true gift is the entirety of herself, her body in motion with the man’s. Even her orgasms are not just physical but whole-body events, felt in the lungs, the thighs, the fingertips, the tongue. She gives all of herself completely.

Frida Khalo was betrayed by her own sister and all that was left in the painting was the mutilated image of the self. Because it was always expected for men to be lawless whores.

The mutilated woman was what Frida Kahlo paints in A Few Small Nips.

Painted in 1935, Unos cuantos piquetitos was Frida’s response to the most devastating betrayal of her life: her husband Diego Rivera, having already slept with models, friends, and other women around the studio, had now slept with her sister, Cristina. Her confidante. Her blood. Her other self.

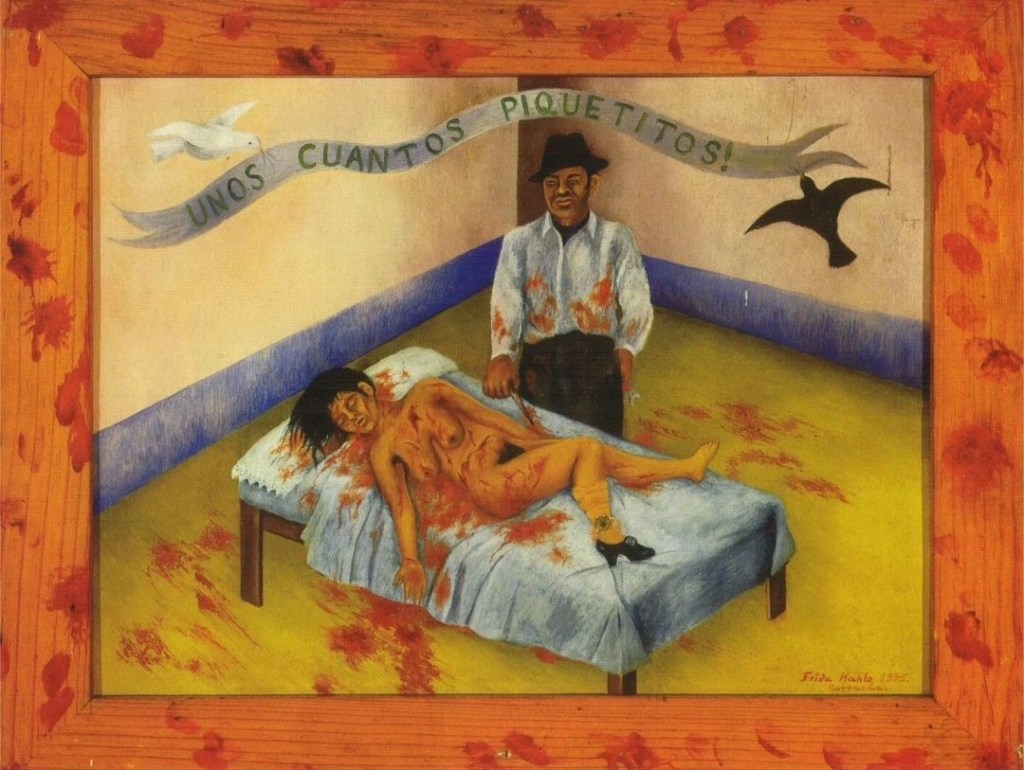

There is no explosion in this painting. No scream. The woman lies slack on a blood-soaked bed. Her face is marked not with exhaustion. Her black hair fans out across the pillow like it’s floating in water. Her eyes are half open, glazed, staring downward, not at the man standing over her, but at a gash on her wrist. A gash she did not make but was made to look like she made it.

She wears one shoe, and on the other foot, an expensive stocking curled gently down her calf. Her toenails are painted red. You can see she was once dressed and made to be beautiful before the violence. The man wearing a hat standing next to her with an amused expression and blood-stained sleeves and a knife in his hand, turned her body into a canvas of cuts. The expression in the painting is designed to resemble a very personal reaction one observes from someone they’re familiar with, intimately.

His face is clean. Unbothered. Beneath his white button-up shirt is the color black. The blood is everywhere: on the bed, on the sheets, splattered on the floor. But the walls remain untouched, closing in on the couple. Still. Quiet.

In another story –

The title, written in Frida’s signature, is drawn from a real-life news story in the Mexican press. A man murdered his girlfriend in a jealous rage. When arrested, he told the police, “It was just a few small nips.” Frida read this and fused personal and political, making the woman’s murder her own. The lover’s excuse becomes the punchline of the entire painting, a slab of irony written on a ribbon with doves carrying it like a holy message.

Feminist aesthetics has long understood Frida Kahlo’s work as a direct rebuttal to patriarchal forms of beauty and value. Where modernist painting often tried to transcend the personal, Frida dove straight into it with use of bright color and texture. Her symbols of trauma and repression are used in corsets, beds, hair, knives, monkeys, blood. She wasn’t interested in the beauty of the self but the beauty of expression. She made the body political, the wound visible, the bedroom into a story. She worked in folk forms, ex-voto styles, and self-portraiture that was immensely blunt.

A Few Small Nips is a raw, messy, deliberately grotesque painting. In making this painting so, she refuses the conventions of “good taste” and constructs an image of feminine pain that is neither romanticized nor easily consumed.

Which brings us to the male gaze, and its intentional subversion. In traditional art history, women are so often painted to be looked at… mostly decorative, nude, passive, and soft. Frida takes that idea and sets it on her own terms. This nude is not erotic because the nude is victim, witness, corpse, and symbol all at once.

In the painting the nipples are visible, yes, but they are not fetishized. They are incidental and crucial to show the body’s stress towards the act of mutilation. The viewer becomes complicit, not satisfied. What we see is not sex. We are not invited to possess her or mourn her. We are invited to feel what she’s feeling.

The blood on the canvas is not contained. In some versions of the painting, Frida even extended the red paint onto the frame and added knife marks to its surface. The violence spills outward, rupturing the separation between art and life, image and viewer. The metaphor becomes tactile as she dares you to hang it in your home.

What haunts me most is not just the imagery, but the movement. The way everything feels like a gasp. The breath held in the woman’s mouth. The smirk on the man’s face. The room itself refusing to react. This is what betrayal often feels like—quiet and ruined in the face of true love.

Frida stabbed her husband and her sister when she painted a murder. She created a wound. One she knew would never stop bleeding in the eyes of who knew what happened to the ones who will find out.

And she named it, with unbearable precision: A Few Small Nips.