My relationship with New Sincerity is a bildungsroman. It began in high school, sometime in the early 2000s, when I first read Norwegian Wood by Haruki Murakami. At the time, I couldn’t articulate what exactly made my chest ache when Toru Watanabe wandered Tokyo, weighed down by memory and emotional ambiguity. I only knew that something about that ache felt familiar. I was a closeted young woman, quietly gay. The world I lived in didn’t quite welcome declarations. Of identity, of longing, of sadness. And so, I gravitated toward the soft melancholies of a literature that hummed gently through isolation, memory, and emotional sincerity.

“Memories warm you up from the inside. But they also tear you apart,” Murakami would write in Kafka on the Shore, and it became something of a private scripture. At the turn of the millennium, it felt like something had broken open. Maybe it was 9/11, or the slow and painful realization that the internet was real and would never turn off. There was an immeasurable sadness in the air, a collective breath held too long. Yet, it wasn’t necessarily despair. Not yet. If shit happened, and it often did, then maybe something good might come of it. That was the undercurrent of my adolescence: not revolution, not resistance, but a quiet optimism underwritten by discomfort. There was no deep, seethed darkness toward systems of control. Not yet. That would come later, when irony gave way to despair, and despair gave way to memes. But in the years between ’00s and the late ’10s, there was a lingering cultural mood based on ‘trying’.

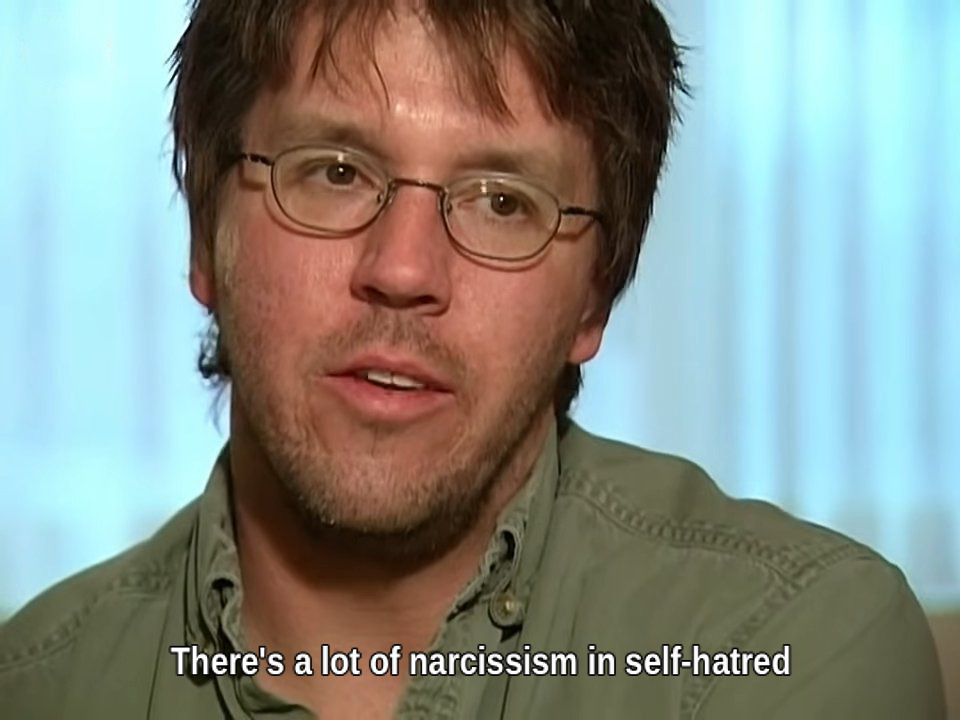

This is what we call New Sincerity. It emerged as a soft rebellion against the hardened edges of postmodernism. Where postmodernism delighted in irony, detachment, and pastiche, New Sincerity aimed for emotional clarity without falling into naïveté. David Foster Wallace, in his prophetic essay “E Unibus Pluram,” wrote that the next real literary rebels would be those “who treat plain old untrendy human troubles and emotions with reverence and conviction.” He added that they might be “willing to risk the yawn, the rolled eyes, the cool smile, the nudged ribs… to risk accusations of sentimentality, melodrama… to risk the suggestion that they’re somehow ‘unhip.’”

Writers like David Foster Wallace, Zadie Smith, Dave Eggers, Jonathan Safran Foer, and Miranda July leaned into vulnerability. They brought back earnestness, emotional introspection, and moral seriousness, although always with self-awareness. Their work could be funny, strange, and elliptical, but never detached from the question of how to live. It was not a rejection of postmodernism but a deepening of it, a desire to keep the critical lens while letting emotion breathe through the glass. For many of us, it felt like an invitation to be honest. Not with capital-T Truth, but lowercase-truths. The bruised, the banal, the beautiful.

In the early 00s, reading a book still felt intimate. The internet didn’t offer brand deals yet. People still read for pleasure. If they didn’t read novels, they read blogs. They read magazines. They read the New Yorker. Reading wasn’t commodified book recommendations yet. It wasn’t performance, yet. There were no Goodreads infographics or BookTok hauls, yet. You read something and passed it to a friend with dog-eared pages. “We read to know we’re not alone,” William Nicholson wrote in Shadowlands, and in that era, it still felt true. New Sincerity lived in the spaces between physical books and early digital life. Blogs became a sort of sincerity workshop. A stranger could write, “I miss my dad today,” and 12 commenters would respond with personal anecdotes and links to music. It was a pocket-sized, imperfect utopia of self-expression.

Musically, this sincerity manifested in what critics often called “sad indie” or “emo-adjacent,” through bands like Death Cab for Cutie, Bright Eyes, and The Postal Service. Their lyrics were personal, obsessive, almost diaristic. They didn’t shout slogans. They whispered long sentences. “I wish the world was flat like the old days, then I could travel just by folding the map,” sings Ben Gibbard in “The New Year,” and it’s almost funny how many of us folded into that sentiment like paper. Let’s be real. Everything is post-punk if you reflect on it hard enough. The musical lineage that fed New Sincerity was introspective and guitar-based, but always leaning into earnestness. These bands rejected rock-star cool. Their pain wasn’t glamorous. It was anxious, mundane, suburban. And in that mundanity, many of us found comfort in each other.

It’s corny, maybe. But it was also formative. It made men read, yes. But it also encouraged girls to take their interiority seriously. To not just feel things, but to learn how to frame them. To reach for language, for theory, for style. And intelligence, in that cultural moment, wasn’t something to be consumed or worn like an iron on patch. It was a shared pursuit. “Be so good they can’t ignore you,” Steve Martin once said, and that line floated around creative circles like a dare and a blessing. We sought out novels that explained our ache. We posted fragments of Hafiz, Rilke, or Joan Didion. We filled notebooks with quotes, feelings, and dick doodles. We annotated Everything Is Illuminated or The History of Love. We didn’t know what we were doing except trying to find some structure for our yearning. “We live our lives, do whatever we do, and then we sleep – it’s as simple and ordinary as that,” wrote Murakami in After Dark, and even that ordinariness felt profound in our hands.

By the late 2010s, New Sincerity began to fade. Something shinier, faster, more self-conscious, and self-limiting came after. Social media hollowed out the sincerity it once enabled. Authenticity became an aesthetic, a brand pillar, a marketing strategy. The deep longing that defined early sincere media turned into bite-sized “vibes.” But some of us never stopped longing. Some of us still write as if people are listening carefully. Some of us still underline books and write essays about it. For those of us who lived through its first wave, the effects are lingering. We still believe in the novel as a home we can stay in. We still write long paragraphs about the ourselves and post it. We still hope that if we say something honest enough, it might open a small door in someone else’s chest. We still reread those books. And we still remember how they made us feel, back when the world was a little quieter, less connected, and our feelings had somewhere to go.

“Try to learn to let what is simply be,” David Foster Wallace once wrote in Infinite Jest.