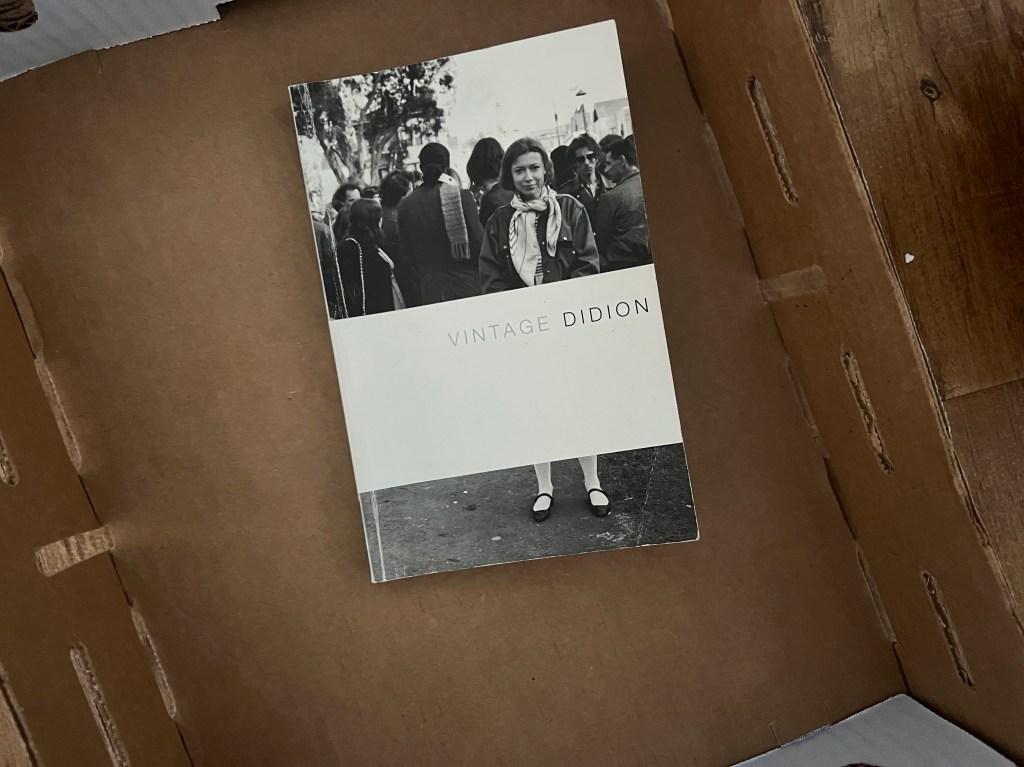

In the interest of maintaining fidelity to my own stated intent, that I would attempt to live a life less mediated by the gloss of screens and notifications, I reached, almost ceremoniously, for my old Vintage edition of Joan Didion. A collection of essays, varied in subject and geography, lay within. Each essay presented itself not so much as a self-contained argument but as a sedimented fragment of time, location, and mood. There was a strange but deliberate architecture to the sequence. What might have begun as journalism had, through a series of carefully wrought compressions and expansions, been made to cohere into something nearer to narrative art.

The voice, Didion’s characteristic clarity and chill, did not so much recount events as subject them to a method of private alchemy. A mood was conjured, not just meaning. There was a laconic elegance in how the pieces unfolded, each one coiled around an unstated thesis that one could almost sense in the negative space.

What unsettled me, or perhaps fascinated me more deeply than I had expected, was the sense of having read it before without possessing the memory of doing so. I discovered notes, penciled faintly in the margins and tucked between the pages: cryptic, elliptical, and undeniably mine. They read like the marginalia of a person I once was, but can no longer fully recall. The handwriting was familiar. The thoughts, slightly less so. It is a curious thing to be haunted by one’s own intellectual residue.

I do not know if I will remember this reading either. There is an irony in that. To read Didion is, in part, to reckon with memory’s failure to order the self. Perhaps the forgetting is part of the practice.