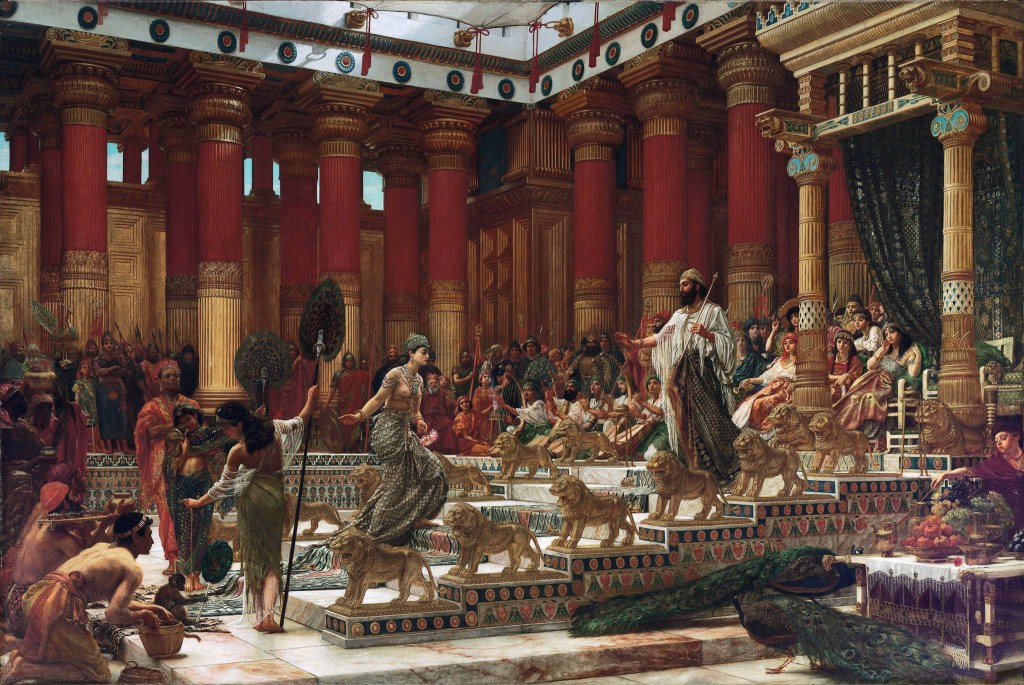

image: The Visit of the Queen of Sheba to King Solomon (1890) , Edward John Poynte

Filed Under: I had nothing better to do because I shat myself and now I’m giggling.

I first encountered Jordan Peterson’s work under the impression that I was approaching a myth critic in the lineage of Joseph Campbell or Northrop Frye, someone who approached religious and narrative texts as symbolic scaffolding for the self. Peterson’s lectures on the Bible, his invocation of archetypal figures, and his biological analogies, such as the infamous lobster, seemed at first to gesture toward a synthesis of depth psychology and mythopoetics. What I found instead was a sustained collapse of critical inquiry into reactionary apologetics. His project weaponizes mythology not to enrich our understanding of the human condition but to justify existing power structures and anxieties.

The disappointment is not merely aesthetic but philosophical. Peterson operates under the guise of dispassionate inquiry, but his rhetorical mode is one of ideological conviction masked as academic neutrality. In his lectures, he treats biblical stories and Jungian archetypes as ahistorical truths rather than as textual artifacts situated in specific epistemic and cultural traditions. The effect is a fundamentalist hermeneutic presented in a secular form. Whereas Joseph Campbell, in The Hero with a Thousand Faces, conceives myth as a transformative and pluralistic journey—“The hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder”—Peterson’s interpretation is prescriptive, didactic, and moralizing. The hero’s journey is no longer about transcendence or initiation into mystery. It becomes a behavioral imperative: clean your room, return to order, resist chaos. The journey terminates not in transformation but in obedience.

This is a profound distortion of mythopoetic thinking. Campbell’s comparative mythology invites us to see how cultures negotiate the unknown through story. It foregrounds ambiguity and contradiction, not resolution. Northrop Frye similarly resists literalism, emphasizing in Anatomy of Criticism that “myth is the matrix of literature; it contains what we may call the total form of human imagination.” Frye’s structural approach distinguishes between the mythic and the ideological. Myth functions as a framework for pattern recognition, not as an apparatus for social conformity. Peterson, by contrast, collapses metaphor into moral ontology. In his vision, the feminine becomes synonymous with chaos, the masculine with order. This gesture reduces symbolic language to fixed binaries and reinscribes patriarchal norms through symbolic misreading.

Theodor Adorno’s critique of cultural regression is instructive here. In The Culture Industry, Adorno warns of how aesthetic forms lose their critical potential when subsumed under commodity logic. What Peterson offers is a form of what Adorno would call “pseudo-culture,” a simulacrum of thought that traffics in seriousness without the substance of dialectical critique. Peterson’s mythologizing does not illuminate but rather aestheticizes ideological commitment. His frequent lament about the loss of meaning in contemporary life—his fear of “ideological possession”—mirrors precisely the kind of regressive desublimation Adorno describes, in which cultural products masquerade as emancipatory while reifying alienation.

This is especially evident in Peterson’s popularization of Jungian thought. Jung’s archetypes, at their best, are meant to engage the psyche’s symbolic richness. But Peterson reifies these structures into fixed moral categories. In his work, the shadow is not a call to integrate the unconscious but a coded warning against political radicalism. The anima is not an invitation to wholeness but a symbol of the threat posed by feminism or emotional instability. Rather than using myth to expose complexity, he simplifies it to serve a moral-political agenda. The symbolic becomes schematic.

Slavoj Žižek’s confrontation with Peterson in public debate underscores the philosophical vacuum at the heart of Peterson’s project. Žižek rightly critiques Peterson’s obsession with “postmodern neo-Marxists,” a term so conceptually incoherent it dissolves under scrutiny. There is no unified intellectual movement that corresponds to this bogeyman. Žižek, who straddles Lacanian psychoanalysis and Hegelian dialectics, recognizes that ideology does not function by providing clear enemies or solutions but through symptomatic contradictions. As Žižek writes, “Ideology is not simply imposed on ourselves. Ideology is our spontaneous relationship to our social world.” Peterson’s insistence on radical individual responsibility as a cure for all malaise precisely enacts this ideological fantasy. It individualizes structural crises and offers moralism where critique is needed.

Moreover, Peterson’s rhetorical style, marked by emotional volatility, frequent tears, and escalating tone, further betrays the posture of disinterest. Genuine scholarship requires what Pierre Bourdieu called “epistemic vigilance,” a refusal to collapse the object of study into the needs of the self. Disinterest, in this context, is not apathy but a methodological stance. It is the capacity to hold one’s own desires and investments in suspension in order to let the object disclose itself. Peterson does the opposite. His readings of myth are always in service of a personal ethos. This is not analysis; it is projection.

This return to the self is not without cultural consequence. Peterson’s work has found an audience among young men, particularly those disoriented by shifting norms of gender and authority. What he offers is not a rigorous engagement with the symbolic world but a therapeutic-patriarchal balm. The language of myth and responsibility becomes the grammar of resentment. The manosphere’s embrace of Peterson is not incidental. It is a logical extension of his thinking, in which structure trumps imagination and vulnerability is cast as pathology. As Adorno warned, “What is decisive is not the moral question of the individual’s guilt, but the tendency of society.”

In this light, Peterson cannot be regarded as a public intellectual in the tradition of the myth critic or cultural theorist. He is, rather, a symptom of a moment when crisis becomes branding and anxiety is metabolized into content. The tragedy is not that Peterson failed to live up to Campbell or Frye. It is that he actively reversed their projects. Where Campbell opens the door to transformation and Frye to structure without dogma, Peterson offers closure. His myth is not the hero’s journey, but its foreclosure.

I engaged with his work thoroughly, not to dismiss it reflexively, but to understand its allure and its limits. I hoped for inquiry and found apologetics. I hoped for disinterest and found a man at war with symbolic ambiguity and himself. I finish his lectures with the same sense I imagine many of his readers feel without naming it. Something vast has been collapsed into something small. A discipline has been reduced to a platform. The myth of the self, once a call to adventure, has been repurposed into a sermon against uncertainty.

Damn you! – Frasier Crane

Sources

- Adorno, Theodor W., and Max Horkheimer. Dialectic of Enlightenment. Translated by Edmund Jephcott, Stanford University Press, 2002.

- Adorno, Theodor W. The Culture Industry: Selected Essays on Mass Culture. Edited by J.M. Bernstein, Routledge, 1991.

- Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. New World Library, 2008.

- Frye, Northrop. Anatomy of Criticism: Four Essays. Princeton University Press, 2000.

- Jung, Carl G. The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Translated by R.F.C. Hull, Princeton University Press, 1981.

- Peterson, Jordan B. Maps of Meaning: The Architecture of Belief. Routledge, 1999.

- Peterson, Jordan B. 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos. Random House Canada, 2018.

- Žižek, Slavoj. The Sublime Object of Ideology. Verso, 1989.

- Žižek, Slavoj. Living in the End Times. Verso, 2010.

- Žižek, Slavoj, and Jordan B. Peterson. Žižek vs. Peterson: A Debate on Happiness, Marxism, and Capitalism. 19 Apr. 2019, Sony Centre for the Performing Arts, Toronto. Public debate.