It is June, and I have read one new book.

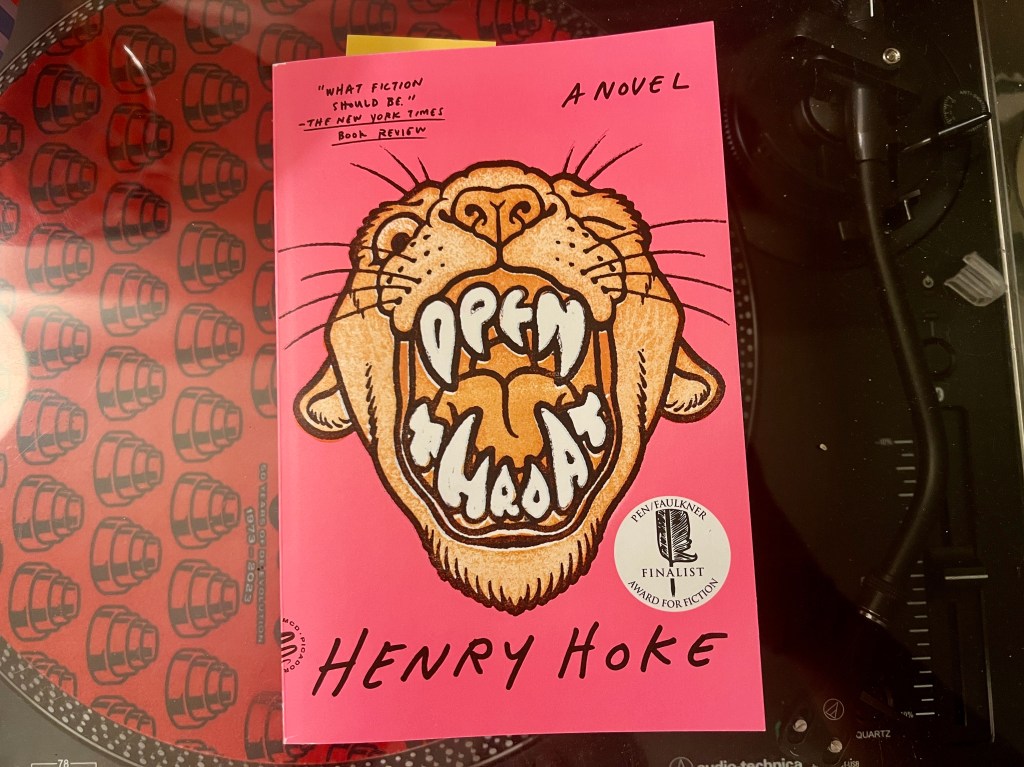

This statement is not made in shame, but with a kind of clarity. One spends so much time among fragments—headlines, feeds, flickers of text—that the act of reading a whole book, from beginning to end, becomes almost mythic in scale. I hadn’t read a book in a long while. And yet Open Throat arrived not as a demand, but as a kind of welcome intrusion. It did not feel like a book in the traditional sense, which may be why I could bear to finish it. It felt more like an epic in tatters: haunted, indirect, hungry.

Henry Hoke’s Open Throat presents itself as a novel, but it is closer in spirit to the fragmentary epics of late antiquity or the lyric confessions of a creature straining to speak across a linguistic divide. Its narrator is a mountain lion, genderless, unnamed, orphaned into language, who prowls the margins of Los Angeles. What we are offered is not plot, but perception. The lion watches, listens, digests. It speaks in unpunctuated lines, somewhere between free verse and fever dream, its voice shaped by proximity to humans yet estranged from their comforts and conventions.

To say that the lion “develops human consciousness” is almost accurate, but imprecise. It is not that this creature becomes human. Rather, it becomes aware of the great, grinding machinery of humanness: the posturing, the cruelty, the petty rituals. It finds in certain people, especially the unhoused, a kind of fellow exile. The lion, in its liminality, recognizes those who are also betwixt and between. These moments are deeply moving not because they anthropomorphize the lion, but because they deconstruct the assumed coherence of the human.

Open Throat exists in the tradition of the bestiary, the beast that sees more clearly than man because it is not bound by man’s delusions. But unlike the allegorical animals of medieval literature, this lion is corporeal, suffering, embodied. Its hunger is literal and existential. Its observations verge on the sacred. One thinks of Coetzee’s creatures or of Clarice Lispector’s Hour of the Star, where the narrator’s alien gaze is also a kind of mercy.

It is tempting to call Hoke’s book “easy to read,” but this simplicity is an illusion. The language is stark but layered; the lines are brief, but the emotional freight is immense. The lack of punctuation evokes breathlessness, urgency, and perhaps an animal’s struggle to shape thought into speech. This fractured style was not only accessible to me as a lapsed reader, but welcoming. It permitted my own fragmented attention to find a foothold again.

In returning to books, I did not expect to be ushered back by a lion. But Open Throat met me where I was: halfway between habit and hunger, silence and story. It reminded me that even a creature at the edge of language can tell the truth about a city, about cruelty, about care.