First, I feel compelled to admit—though not confess, because that would imply atonement I’m not yet ready to enact—that I have been struggling to read. Not just to read as one opens a book and follows its trail, but to remain within that realm long enough for thought to deepen and echo. This is not quite the place for that revelation; the more vulnerable cartography of my reader’s drought deserves a separate entry, if I ever remember to write it.

The fact remains: after graduation, I should have read more. I should have approached the architecture of my attention with more reverence and curiosity. But in truth, I gorged on media with the frantic hunger of someone who cannot taste what they consume. The consequence is subtle—like erosion—but it is total. And now, disappointed, chastened even, I return not to literature as a home but as a hypothesis.

Which brings me, strangely but inevitably, to Society of the Spectacle by Guy Debord. I speed-read through it—an irony not lost on me. A book about the acceleration and fragmentation of meaning, consumed in the very mode it warns against. Still, something caught. To aid my own memory, and perhaps to better explain what I mean, I want to plant an example here: the phenomenon of Insta-Poetry.

I have observed Insta-Poetry for years with a mix of anthropological interest and literary frustration. Though I will not, at least not here, defend it, I do wish to consider it seriously—as one might consider a culturally significant weather pattern. It is not, I believe, an evolution of poetry so much as its simulation. What Debord would call a spectacle: a representation that replaces reality with a copy so prevalent it becomes indistinguishable from truth.

Insta-Poetry, typified by figures like Atticus—who rarely appears without a typewriter font and a wistful photograph of a half-nude woman bathed in honeyed light—functions not as poetry but as an aesthetic gesture. The form is spare, the language intentionally vague, aphoristic, even epigrammatic. Consider this from Atticus:

“Love her but leave her wild.”

“We are made of all those who have built and broken us.”

These are sentiments, perhaps even comforting ones, but they are not poems in any formal or rigorous sense. They lack the torque of metaphor, the weight of musicality, the slow alchemy of revision. They are images in textual form—designed to be liked, screenshot, shared. They function as products, not utterances. And as Debord might argue, their function is to pacify rather than provoke.

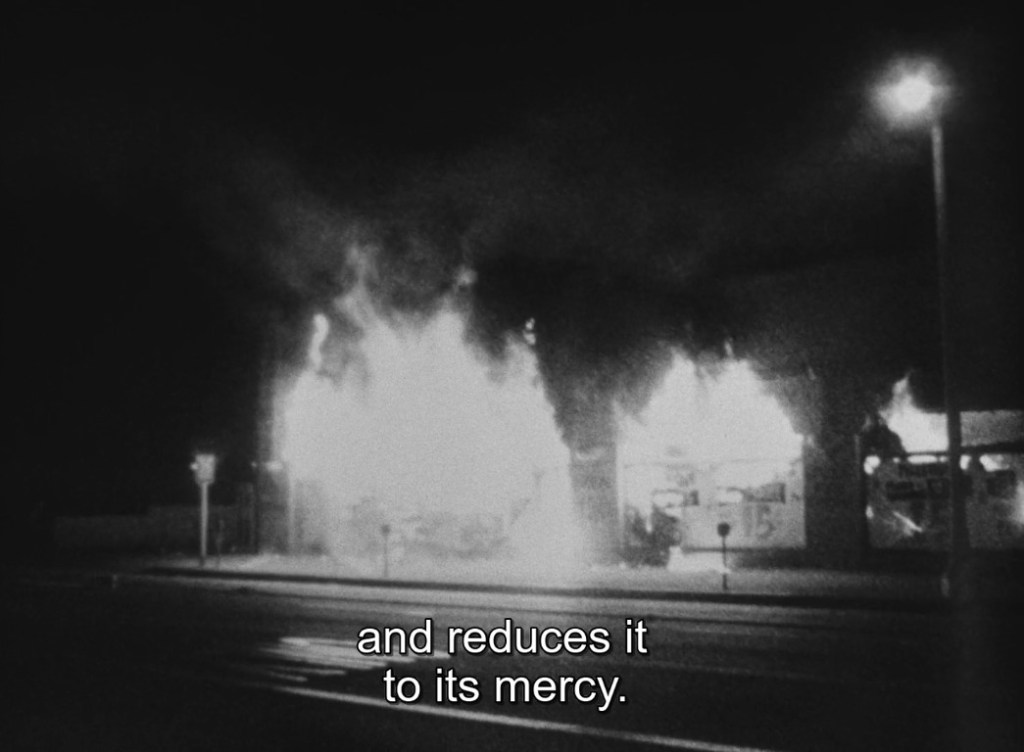

In Society of the Spectacle, Debord writes:

“The spectacle is not a collection of images, but a social relation among people, mediated by images.”

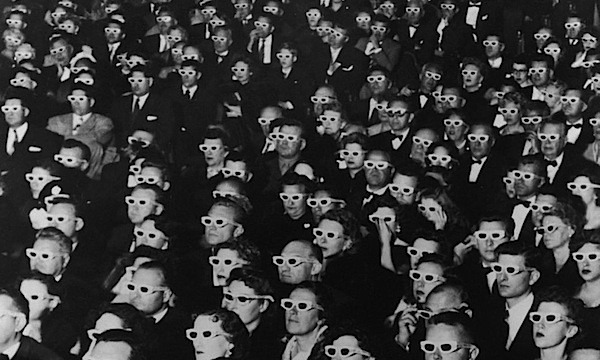

This is precisely the economy in which Insta-Poetry operates. It is performative not only because it is composed within a performative space (Instagram, TikTok, the book-as-quote-machine) but because it relies on audience interpretation to complete its meaning. Its ambiguity is a feature, not a bug. It allows the reader to feel seen without being challenged. The labor of interpretation is minimized, and the labor of composition—true poetic labor, with its drafts, its failures, its lineage—is elided entirely.

In its most absurd and telling iteration, the Insta-Poet proudly appends “New York Times Bestselling Author” to their Instagram bio, to their website banners, to the spines of their books like an inheritance. This too is spectacle: the celebrity status of the poet now replaces the poetry itself. As Debord observed, in the spectacle, the image of the celebrity becomes more real than their actual work. The title “bestseller” becomes a credential not of literary merit but of mass recognition—and through recognition, perceived authority. One need not read the poems, merely acknowledge that others have. Sales replace scrutiny. Publicity replaces critique.

And here we encounter another, perhaps more insidious, tendril of the spectacle: the commodification of education itself, or more precisely, the aestheticization of having been educated. We are living in an era in which certain reading habits—annotated margins, broken spines, tote bags bearing Virginia Woolf—are not tools of scholarship but signifiers of cultural capital. To be “well-read” is no longer a condition of intellectual engagement but a visual motif. And publishers, institutions, and elite schools are all too willing to participate in this sleight of hand.

Through this lens, we see Debord’s theory in full relief: the spectacle does not merely pacify the proletariat with images—it makes them believe they possess power through consumption. In the realm of literature, this means that buying the book (especially the right book, the trending book) becomes an act of social participation. Enrolling in school becomes synonymous with purchasing prestige. One need not read Ulysses, one must only own it—or better, photograph it.

Education, once transformative, is now a brand. And when it is branded, it can be sold. Schools receive more funding, publishers receive more sales, and the illusion of upward mobility is sustained, even as the foundations beneath it decay. The labor of critical thought is outsourced to the marketplace.

The accessibility of Insta-Poetry is often framed as a triumph over elitism. And yet, paradoxically, it participates in the same economy of exclusion—only now it excludes complexity, slowness, and form. It mistakes brevity for democracy. It forgets, or never knew, that the discipline of poetry is not in its length, but in its compression. That brevity is not the absence of thought but its distillation.

The last great attempt to democratize poetry in a meaningful way was spoken word. It had its excesses and affectations, yes, but it insisted on voice and embodiment. There was breath in it. A cadence. A confrontation. Insta-Poetry, by contrast, is a muttered aside in a bathroom mirror—an image of profundity, not its experience.

If I am being honest, the most successful poetic form in contemporary popular culture is music. Lyrics still wrestle with meter and metaphor, still inhabit the rhythms of the body and the ritual of sound. They endure scrutiny. They risk failure. They attempt, at least, a kind of depth.

Insta-Poetry cannot endure scrutiny. It is designed to vanish in the scroll. It thrives on glance, not gaze. And in this way, it fulfills Debord’s prophecy. It is not merely spectacle; it is the triumph of the spectacle over literature. And what’s worse, it tells us that poetry is easy, even effortless. That one need only feel to write. That craft is unnecessary. That the poet is not a worker but a brand.